“Many of West Virginia’s best and brightest students are from rural and underserved areas of our state,” Jennifer Plymale said, describing students at Marshall University’s seven-year BS/MD program. “Through our high school pipeline program, we’re able to identify these exceptional students and offer mentoring and service opportunities. We have found that our students have a heart for service and are very committed to giving back to their community.”

Jennifer Plymale.

Plymale, director of Marshall University’s Robert C. Byrd Center for Rural Health, is an associate dean of admissions at the university’s Joan C. Edwards School of Medicine. She also serves as the director of the university’s BS/MD program. She said that students who successfully complete the Bachelor of Science degree requirements will receive tuition waivers for medical school.

“The program meets the university’s mission to create a workforce for our region,” she said, noting that the program takes 10 students each year.

What’s a Baccalaureate-MD Program?

Also referred to as a combined program or an accelerated program, baccalaureate-MD programs are programs that offer high school seniors a college degree combined with conditional acceptance into medical school, as long as certain medical school admission requirements are met: for example, a minimum score on the Medical College Admission Test®. Most U.S. combined programs range from six to eight years.

According to a 2021 historical review of medical education in the United States, the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) encouraged this model of combining a collegiate degree with medical school as early as the 1920s. At that time, the programs were seen as models producing more physicians more quickly — and with less expense, saving a year or two as compared to the traditional pathway of four years of college followed by four years of medical school. Another review shared that during World War II, all but a few of the nation’s medical schools adapted some type of accelerated program and did so by eliminating summer breaks. Post-war, however, schools returned to the traditional training interval.

With its 2015 start date, Marshall’s program currently has nearly 30 undergraduates and about 35 medical students. Plymale said that although the program doesn’t have a dedicated rural recruitment focus, since West Virginia is a largely rural state, about 50% of program participants are coming from the state’s rural areas. She shared career choice statistics associated with Marshall’s first cohort.

Marshall University’s BS/MD program’s first medical school graduates, 2022.

“About 50% of our students matched in primary care specialties,” she said, adding that about 30% of students matched to in-state residencies. “Both of these statistics – in addition to community of origin — are important since specialty choice and training location have been proven by research to be strong indicators of final practice type and practice site. We have great faith that when our first cohort complete their residencies, they will either practice in rural West Virginia, in rural areas of nearby states, or, if choosing an urban setting, will be more mindful of the needs of rural patients.”

The 1960s also saw the combined program model endorsed as a way to provide training to meet the “growing need for primary care physicians in rural and underserved communities in particular,” according to the 2021 historical review. However, medical education experts pointed to a 2021 analysis of an AAMC survey of over 115,000 combined program graduates from 2010-2017. The report found that that these graduates are neither more likely to have an intention to care for underserved populations nor to practice in an underserved area. However, they are more likely to choose a primary care practice.

Yet, rural medical education leaders like those at Marshall University — and the University of New Mexico — are finding that these programs can be specifically designed to effectively and cost-efficiently mentor and monitor the education process in a way that ensures a pipeline of competent future physicians most likely to meet the workforce needs of rural America.

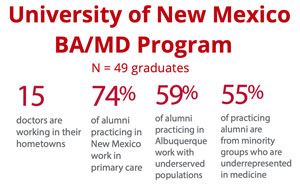

In contrast to the 2021 analysis, the University of New Mexico’s (UNM) BA/MD program has sustained results proving that its students are intentionally serving populations living in rural and urban underserved areas. With a specific rural focus since 2006, program leaders pointed out that of the first several cohorts numbering nearly 50 practicing alumni, 75% are providing primary care and almost 70% have remained in New Mexico. Additionally, twelve physicians are serving in rural counties and 15 work in their hometowns.

In contrast to the 2021 analysis, the University of New Mexico’s (UNM) BA/MD program has sustained results proving that its students are intentionally serving populations living in rural and urban underserved areas. With a specific rural focus since 2006, program leaders pointed out that of the first several cohorts numbering nearly 50 practicing alumni, 75% are providing primary care and almost 70% have remained in New Mexico. Additionally, twelve physicians are serving in rural counties and 15 work in their hometowns.

Robert Sapién, MD.

UNM’s BA/MD program is a partnership between the school’s College of Arts & Sciences and School of Medicine. Robert Sapién, MD, associate dean for admissions at the UNM medical school, is the BA/MD program director on the medical school side of the program. He shared that their program, compared to other U.S. combined programs — which, according to the AAMC, number around 50 — is unique with its rural-focused mission, its rural student recruitment focus, and a large cohort of 28 students per year.

“Simply put, no other combined program looks like ours,” he said.

The program’s executive director, Valerie Romero-Leggott, MD, said the program also aims to have participants representative of New Mexico: a state that she pointed out is largely frontier, struggles with poverty, yet is “amazingly rich because of our multi-cultural traditions, languages, and peoples that create one of the most ethnically diverse states in the continental U.S.”

Valerie Romero-Leggott, MD.

Romero-Leggott said that students have come from 30 of the state’s 33 counties and broadly match the race and ethnicity of the state: about 50% Hispanic/Latinx and the third-highest proportion of Native American population.

“This program acknowledges the social determinants that impact getting a college and medical education,” she said. “It’s offering an amazing opportunity for students from rural and frontier New Mexico, including minority students and those who are first generation to attend college. These students further enrich our educational environments as well as the future health and well-being of New Mexico.”

Debbie Curry.

Both programs indicated that direct high school student recruitment is essential. UNM has program-dedicated recruiters who travel the state. Marshall’s Debbie Curry, the Byrd Center for Rural Health outreach director, described their recruitment activities. She said that prior to their new combined program, she’d enjoyed healthcare pipeline recruitment for several years traveling miles and miles across West Virginia to its rural areas. However, with the BS/MD program’s 2015 start date, she quickly developed an awareness that recruiting for the combined program needed to be different.

“I was at a very rural school talking about medical school,” Curry shared. “The guidance counselor stopped me afterwards and explained that many students are dealing with difficult family or socioeconomic issues and college or medical school can seem very far away and impossible to achieve.”

Curry explained that the guidance counselor’s perspective was invaluable to their recruitment efforts. Instead of just focusing on medical school when talking with students, she needed to discuss an achievable and comprehensive pathway for rural and underserved students to make the transition from high school to college and, eventually, to graduate school.

She and Plymale developed a county-by-county strategy. Using a “community first” approach starting with community leaders and county school board meetings, parameters guiding those pipeline presentations now match the unique culture of each school. She said this avoided the sense of imposing information on students and these presentations allow students to envision themselves as able to follow the path to medical school if they had the desire.

“We don’t just go in and say, ‘You should do medicine,’” Curry said. “Instead, we talk about the fact that they could do medicine. We start with the basics. We talk about how choices made in high school can either help them or derail them. We talk about interviewing. We practice interviewing with them. We’ll talk about what the first day of college looks like, what the first week might look like.”

Robert C. Byrd Center for Rural Health Community First and County-Specific Recruitment Strategy

Program leaders engage with stakeholders to gain insight into local culture and resources, some of whom are listed here:

Although the New Mexico and West Virginia programs have had successful recruitment using their specific approaches, both said their best recruitment strategy are the program’s students themselves.

Marshall’s Curry shared an example.

“Many of our BS/MD students are from tiny rural schools,” she said. “When we go back for awards programs — or if a past student awardee from that community can present a new award to another student — that whole community sees that student receiving a tuition waiver for four years of med school. That sends a message to the community and to other students: ‘You can do this, too. You can pursue your dream.’”

UNM has their own example. Romero-Leggott said that although their students don’t serve as recruiters, they become role models in their communities, providing inspiration and sharing experiences with younger students.

“They are so dedicated to wanting to give back to New Mexico communities, they want others to know about this incredible program and opportunity,” she said. ‘We realize they actually become the best ambassadors for our program.”

Program experts pointed out that funding can’t just include tuition waivers for either undergraduate or medical school, it must support the educators delivering the program, along with administration costs. Marshall’s program is funded by dedicated university funds. In contrast, the UNM program receives state funding. Its leadership team made annual funding request visits for the first 8 years of the program to receive recurring funding for each of those eight years of the program. Romero-Leggott said in those early years, both the state’s House and Senate recognized the program. However, she said she and her colleagues felt legislative support went even a step further.

“I’d like to paraphrase the late House leader, Representative Larry Larrañaga’s comments when the BA/MD program was honored on both the House and Senate floors many years into the program,” Romero-Leggott said. “This leader said, ‘We don’t always get things right in this legislature. We often follow party lines and go at it that way. But I’m very proud to say that we did get it right with this BA/MD program. We have come together as a legislature to really make a difference for the health and well-being for the people of New Mexico.’ We program leaders are very grateful for the generous state funding these legislators made happen. We believe our program has exceeded expectations and can continue to do so.”

Combined Program Student Support

For their undergraduate degree, New Mexico students receive a “last-dollar scholarship”: Any remaining fees not covered by students’ personal state and university scholarships awards will be covered by the program to ensure that the full basic educational cost of tuition, fees, textbook stipends, housing, and meal plan is covered. Marshall University student support exists in the manner of tuition waiver for medical school.

Although New Mexico leaders said their “last-dollar scholarship” support tries to eliminate this need, both programs highlighted the importance of accommodating student employment opportunities since many students must work either to supplement personal income or to help their families.

Leaders from both programs acknowledged that curriculum design needs to accommodate the psychosocial needs of combined program students who usually begin their collegiate studies around age 17 — the age that marks the beginning of the last five years of adolescence. Additionally, because some education experts have sometimes expressed concern that students from rural are an “at-risk” group, other design elements accommodate the anticipated needs of rural, rural minority, and rural first-generation college students.

Sushilla Knottenbelt, PhD.

Sushilla Knottenbelt, PhD, the director of the UNM program on the College of Arts & Sciences side, said their curriculum purposefully allows for traditional college experiences.

“We want these students to become a cohort that’s involved in developing themselves to become the best doctors for New Mexico,” she said. “Although some have pre-college credits coming in, we’re not setting a bar for students to finish their undergraduate education in three years. Instead, we encourage these students to use enrichment activities to complete their four years. For example, they might study abroad for a semester, complete a second major or dual degree, volunteer or participate more extensively in student activities at UNM, including student governance. Students with fewer college-level credits and less educational privilege will have the four-year time period that provides curriculum flexibility allowing for adjustment to college and, if needed, to retake important courses. Lastly, students are provided with extensive support with dedicated advisors and faculty members.”

UNM BA/MD student’s mortarboard message: “MD to be”.

Marshall’s program also uses a traditional undergraduate curriculum with enrichment activities, but in three years, rather than four.

“We designed the program so that all needed prerequisites could be completed in three years,” Marshall’s Plymale said. “Three years allows for students to have both the academic and life-maturing experiences that happen in college before jumping into the rigors of medical school.”

Plymale and Curry said their program’s enrichment activities include clinically oriented experiences, like suturing labs. However, some are dedicated to social experiences since, at some time, students might compete with other applicants who likely have a broad variety of social experiences. In those situations, they said they know that research proves these non-academic skill differences can actually be stigmatizing.

“The enrichment activities provide a wide array of activities that we feel not only provides them the necessary academic background, but also offers them social and professional experiences that will further prepare them for success in medical school,” Plymale said. “For example, the students were provided with a formal etiquette dinner experience. Our students recognized the activity’s importance and came prepared. However, the event facilitator was clear: ‘This is not about going out to dinner. It is about getting that job.’”

UNM’s program leaders said that with time, their program’s specialized curriculum has demonstrated value not just for the program’s own students, but for students within the university at large and the program’s faculty. Leaders said they view these accomplishments as important for their program’s sustainability — making the case for ongoing financial support — and, perhaps, of interest to other institutions wanting to replicate their program.

One curriculum element in particular — the offering of a major in Health, Medicine, and Human Values that is geared to rural New Mexico and the state’s specific social determinants of health — has proven so useful and popular, it is now offered outside the combined BA/MD program as a minor.

There are additional successes. Because the program also has a dedicated BA/MD undergraduate faculty cohort, program-dedicated educators have created specialized pedagogy innovations for the program’s coursework that have been scaled to students outside the program. UNM program leaders said that informal tracking suggests that these innovations have perhaps even impacted the university’s non-BA/MD STEM curriculum and increased its graduation rates.

A Turnabout: Who Inspires Whom?

Generations of traditional pathway med school-bound undergraduates and medical students have been inspired and influenced by formal and informal mentors, academic and non-academic alike. Research has demonstrated that high-performing students are often influenced away from primary care specialties or a practice dedicated to underserved populations by their mentors. Naturally, a baccalaureate-MD degree cohort is also likely to experience those same influences.

Although not a particularly quantifiable program element, both Marshall and UNM program leaders shared how those influences are seemingly absent. Why? They said they believe it is due to their students’ passion around the academic and social goals of providing primary care and serving rural and underserved populations. They said they have stood back and observed what seems to be a reverse influence: dedicated students have inspired their faculty to help students master coursework that brings competency to the primary care of rural and underserved populations.

Romero-Leggott said that she also believes UNM’s intentional program planning around the determinants and rural practice predictors impact the students and inspire them to be more likely to serve communities of color and underserved communities.

After the first seven years of the Marshall program, Plymale said she’s seen a pattern emerge.

“Some of our students have lived the most challenging circumstances,” she said. “However, they have been resilient. Now, they’re learning that being a physician is also a challenge. They’re learning it can get messy, too. They are the best and the brightest students who have embraced a philosophy of serving others. Something in this program seems to bring that out. Every day we see that service heart and it seems to trigger almost an emotional reaction within faculty. I’ve come to understand that maybe we just need to get out of these exceptional students’ way and let them do something big.”

UNM’s Knottenbelt pointed out another important component of their undergraduate program: the summer rural community practicum, a month-long activity that occurs between the second and third undergraduate year. With a series of weekly seminars covering public health core functions and its ten essential services, the practicum uses a small-team format to execute a community engagement project that includes asset-mapping, an activity that inherently provides learning about a community’s challenges and available resources. The month-long activity wraps up with a formal presentation.

Knottenbelt shared an anecdote about one of those final presentations.

Having alumni in rural practice certainly fulfills the program’s big-picture mission. In addition, to see our alumni giving back to these younger pipeline students is absolutely amazing.

“I went to a recent final practicum presentation in northwestern New Mexico where the students had the opportunity to shadow one of our alumni who is married to another alumna, both of whom serve rural patients including those on the Navajo Nation,” Knottenbelt said. “This summer, we had students at seven different practicum sites and a total of eleven of our alumni participated, either allowing students to shadow in their rural practice, or helping in the circuit rider [mobile faculty instructor] role, facilitating the weekly seminar. Having alumni in rural practice certainly fulfills the program’s big-picture mission. In addition, to see our alumni giving back to these younger pipeline students is absolutely amazing.”

Although the UNM and Marshall combined programs are in disparate locations and differ in maturity, program leaders at both institutions indicated that they are proud that their programs seem to graduate not just physicians but physician leaders. New Mexico’s Sapién said he came to realize that at a recent medical school graduation event.

“Our BA/MD program was well-represented at a recent medical school graduation,” he said. “The student speaker, a student receiving an award, and the students leading the Declaration of Geneva [The Physician’s Pledge], in Navajo and Spanish, were all BA/MD Students. I suddenly realized that our BA/MD students were leaders as I saw them participate as a major part of the entire medical school class graduation ceremony.”

Marshall University’s Plymale said she could not provide a better example of the program’s impact than the words in a letter written to her by one of the program’s graduates, Dr. Kadi Conn, a current resident in Marshall University’s Family Medicine program:

“…I am so incredibly honored to have the opportunity to participate as a member on the other side of this process and I look forward to attending the BS/MD interviews, getting to know the applicants, while providing encouragement or advice…Coming from a very rural background, the majority of my classmates did not automatically go straight into college. If they did have that opportunity, they were lucky if they had the resources to be able to finish.

No one talked to us about medical school — no one ever mentioned that was an option. In fact, my own guidance counselor discouraged me from even bothering to apply. I was told students from schools like ours are never considered for things like that — it would be a waste of my time…Despite the many things that could be seen as working against me, I now know I had things in my favor as well. I have a strong work ethic, an absolute love for people, a passion for service, and an interest in science. I know what it means to struggle, to fail, and to dust myself off and try again… As I progress in my education, I realize more and more the enormity of gratitude I have for this program…Thank you for believing in me, encouraging me, and for doing the same for so many others…”

Additional Resources

For more about the University of New Mexico BA/MD program:

Cosgrove, E. M., Harrison, G. L., Kalishman, S., Kersting, K. E., Romero-Leggott, V., Timm, C., Velarde, L. A., & Roth, P. B. (2007). Addressing Physician Shortages in New Mexico Through a Combined BA/MD Program. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 82(12), 1152–1157.

Clithero, A., Sapién, R., Kitzes, J., Kalishman, S., Wayne, S., Solan, B., Wagner, L., & Romero-Leggott, V. (2013). Unique Premedical Education Experience in Public Health and Equity: Combined BA/MD Summer Practicum. Creative Education, 4, 165-170.

Ballejos, M. P., Shane, N., Romero-Leggott, V., & Sapién, R. E. (2019). Combined Baccalaureate/Medical Degree Students Match Into Family Medicine Residencies More Than Similar Peers: A Matched Case-Control Study. Family Medicine, 51(10), 854–857.